Photographed and written by

John M. Young

I kind of think who ever came up with leather clad pipes either had some structurally sound but ugly briar blocks or they were hallucinating due to taking Ambien and took a break from walking their frozen turkey while wearing a tangerine Speedo and a sombrero long enough to wrap a piece of briar in leather. Yeah, let that vivid mental image marinate before continuing. Either way, they do show up on the estate market and can be pretty pipes. This Jeantet with a faux alligator-skin texture for example is a pretty pipe. Once again, I can’t recall how it came to me other than as part of an estate lot. Below are some photos of the pipe before work began.

The stem showed signs of oxidation and tooth chatter. The stem’s stinger was well lacquered with smoking residue indicating frequent use. The tobacco chamber had a bit of cake and the rim was lava encrusted. The seams of the leather looked good and intact and the condition of the leather, overall, was good. There was some discoloring of the edges of the leather around the rim which I thought would be difficult at best to remove. Overall though the pipe looked like it had great potential.

Background

Jeantet is an old name in briar pipes and harkens back to southern France in the late 1800s. My first stop on the research train was to pipedia.org. Here I found the following:

“The firm of the Jeantet family in Saint-Claude is first mentioned as early as 1775. By 1807 the Jeantets operated a turnery producing in particular wooden shanks for porcelain pipes and wild cherry wood pipes. The firm was named Jeantet-David in 1816, and in 1837 the enterprise was transformed into a corporation as collective name for numerous workshops scattered all over the city.

The manufacturing of briar pipes and began in 1858. 51 persons were employed by 1890. Desirous to concentrate the workers at a single site, the corporation began to construct a factory edifying integrated buildings about 1891 at Rue de Bonneville 12 – 14. This took several years. In 1898 Maurice Jeantet restructured the business. He is also presumed to enlarge Jeantet factory purchasing a workshop adjoining southerly. It belonged to the family Genoud, who were specialized in rough shaping of stummels and polishing finished pipes. (In these times it was a most common procedure to carry goods from here to there and back again often for certain steps of the production executed by dependant family based subcontractors. Manpower was cheap.)

Jeantet was transformed to a corporation with limited liability in 1938. By that time a branch workshop was operated in Montréal-la-Cluse (Ain), where mainly the less expensive pipes were finished. 107 employees – 26 of them working from their homes – were counted in Saint-Claude in 1948 and 18 in the Ain facility.

The Saint-Claude factory was considerably modernized by ca. 1950 installing (e.g.) freight elevators. In 1952 the southern workshop was elevated. 80 workers were employed in 1958. The factory covered an area of 2831 m²; 1447 m² of the surface were buildings.

The climax of the pipe production was reached around 1969, when thirty to thirty-five thousand dozens of pipes were made by 72 workers (1969). But then the production continuously dwindled to only six or seven thousand dozens in 1987 and only 22 workers were still there. Even though, around 1979 a very modern steam powered facility for drying the briar had been installed in the factory’s roofed yard.

Yves Grenard, formerly Jeantet’s chief designer and a great cousin of Pierre Comoy, had taken over the management of Chapuis-Comoy in 1971. Now, to preserve the brand, the Jeantet family went into negotiations with him, and resulting from that Jeantet was merged in the Cuty Fort Group (est. 1987 and headed by Chacom) in 1988 along with the pipe brands of John Lacroix and Emile Vuillard. Chacom closed the Jeantet plant, and the City of Saint-Claude purchased it in 1989. After alternative plans failed, the buildings were devoted to wrecking. The southerly workshop was wrecked before 1992.

Today Jeantet pipes were produced as a sub-brand by Chapuis-Comoy who’s mainstay is Chacom of course.” (Jeantet – Pipedia). If you were wondering, 2831 m² is about 0.7 acres. That doesn’t seem like much by today’s standards but I am sure in southern France that was expansive for its time. I am going to assume that this pipe was made some time prior to the demolition of the Jeantet plant in 1992, that is a pretty easy conclusion to draw. Moor likely it was produced prior to the closing of the plant in 1988.

Leather wrapping of briar has an equally interesting history and again pipedia.org details one of the most renowned leather workers who specialized in pipes. “In 1948 Jean Cassegrain inherited a small shop near the French Theater on the Boulevard Poissonnière in Paris, called “Au Sultan”. Articles for smokers and fountain pens were offered there.

Now, the absolute bulk of the pipes Cassegrain found in the inventory was from war-time production and due to the sharp restrictions on pipe production the French government had enforced in 1940, these pipes were of very poor quality and showed large fills. Strictly speaking, they were not marketable now that the French pipe industry produced pipes of pre-war standards again. In this situation Cassegrain had the probably most enlightened moment in his life: he took some of these pipes to a leather worker who clad bowls and shanks in leather. Only the rims of the bowls and the shanks’ faces remained blank.

E voila – the pipes looked pretty good now and were eye-catching enough to become an instant success in sale. Above all among the thousands of Allied soldiers who populated Paris in those days. The thing worked well, and even unexperieceid pipesters liked the covered pipes very much for they did not transmit the heat to the hand. Very soon Cassegrain had sold the old stock of pipes, and the leather-clad pipes became his only product. He began to place orders with renowned firms like Ropp or Butz-Choquin.

Because the name Cassegrain was already registered as a trade name for one his relatives, Cassegrain, a big fan of horse races, named his newly created firm after his favorite race course Longchamp near Paris. Hence an outlined galopping race horse with jockey was chosen as logo. The wind mill – see the frontpage of the catalog – symbolizes the name Cassegrain.

The numerous contacts with American soldiers bestowed an official contract on Cassegrain to supply the PX shops with his leather-wrapped pipes. According to his grandson, also named Jean and now CEO of the family firm, “There wasn’t an American GI in Europe who didn’t have one of these pipes at the time. They were exported and sold in PXs worldwide. That’s how it all started.”

In the course of the following years Cassegrain enlarged and refined the Longchamp pipe program continuously. More precious kinds of leather like calf and suede came in use. The top range was clad in alligator leather and even pony fur was used. In addition, many models showed vibrant colors now, and small sized pipes, the “Royal Mini”, made that also women interested themselves in the pipes. The hype was pushed furthermore, when well-known persons of public interest, like TV moderators or pop icon Elvis Presley, began to flaunt with a Longchamp put on.

The Cassegrain family expanded their business in 1955 starting a sortiment of pipe bags, tobacco pouches, pipe stands, ashtrays, tampers, lighters – all made of or clad in leather. (Going from there Longchamp turned to other gentleman’s leather-goods around 1960 and finally established itself as a global brand at the end of the 1960’s introducing the Xtra-Bag for ladies.)

After 1970 the interest in leather-clad pipes slowly diminished. The Longchamp pipes were offered for the last time in the 1978 catalog though previously placed orders were delivered until 1980.

The splendid success inspired many other renowned producers to offer their own lines Ropp, Butz-Choquin, Gubbels, GBD, Sasieni… Maybe Savinelli was the very last producing them for the label of the famous designer Etienne Aigner.” (Longchamp – Pipedia). Now there is no reference to Jeantet in the Longchamp article above but, it is pretty easy to imagine that the number of companies specializing in covering briar pipes in leather, with attractive results, would not have been an extensive list. The dates also coincide nicely with the heyday of pipe production during the 1950-1980s period. This would narrow down the production of this particular pipe to a product produced prior to the late 1970s.

The Restoration

After the before photos the pipe made it to the workbench.

The stem was a tight fit and not wanting to force things unnecessarily, I began work on the stem. The stinger was fouled with smoking residue and quite stuck in the stem. I used a strip of thick leather to protect the aluminum of the stinger from the jaws of the pliers.

Well I’ll be, the stinger was threaded. A nice touch showing a higher quality of workmanship than I was expecting.

I dropped the stinger into a medicine cup of 99% ethyl alcohol to soften the residue and proceeded to clean the vulcanite threads of the stem.

The airway of the stem was scrubbed using a nylon shank brush and the ethyl alcohol.

Numerous bristle pipe cleaners joined in the fun of removing the yuck from the airway.

The bite zone of the stem was filed with a small flat file to remove the tooth chatter and reestablish the button.

Below is a close-up of the top surface of the stem after filing.

And the bottom surface also after filing.

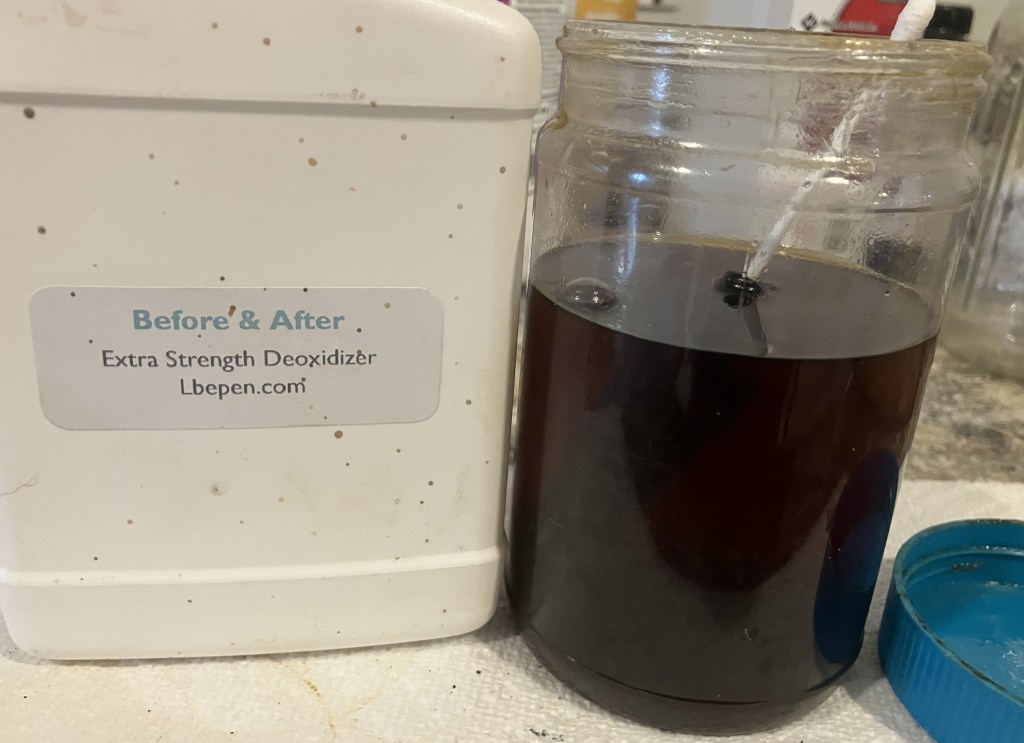

The stem was then suspended into Before and After Extra Strength Deoxidizer (deox). I planned to leave it in the solution for at least 12 hours but more likely 18.

I retrieved the stinger from the ethyl alcohol and scrubbed it with a brass brush, cotton swabs, bristle pipe cleaners, and regular pipe cleaners. It eventually looked pretty good.

I then took the stinger to the buffer to make it look even better by polishing it with white buffing compound. I hoped that I could not launch the stinger across the room as I lost a grip on it.

When, I didn’t lose my grip and the stinger now looked better than good.

The reaming gear was gathered.

The #1 PipNet blades proved too narrow for use but the #2 blades were about perfect.

The “about perfect” did require me to do a bit more clean-up with the Smokingpipes Low Country reamer and the General triangular scraper.

The reaming done, it was time to sand the tobacco chamber and assess for any heat damage.

The sanding was done with 320 sandpaper wrapped around a wood dowel. The bare briar showed no signs of any heat damage. The rim on the other hand, needed a good scraping.

The lava was moistened with saliva and scraped with the edge of a very sharp pocket knife.

I used a wood sphere and a sanding sponge to restore the inside edge bevel and to remove most of the charring from lighting the pipe.

To clean the leather I went looking for my saddle soap. I could have sworn I had some but could find none. After a little research, I discovered that Castile soap could be diluted with water and used as a leather cleaner.

Below is the result of the stummel being scrubbed with the diluted Castile soap. The soap was rinsed with warm water and dried with a cotton hand towel.

I had Mink Oil and Neatsfoot oil. I opted to use the Mink Oil since I liked the smell of it better.

The leather was liberally coated with Mink Oil and the rim with Before and After Restoration Balm. These were allowed to sit for 30 minutes. It was about here that I realized that I had not cleaned the shank airway. DOH!

The excess Mink Oil and Restoration Balm was wiped away using an inside out athletic sock after 30 minutes.

The shank cleaning then began, completely out of order and with extra caution as to not get the newly cleaned leather dirty. A good number of cotton swabs dipped in alcohol were used as was scraping with a dental scraper.

I was pretty sure there was still a good deal of yuck in the airway so a cotton/alcohol treatment was prescribed. The bowl and airway were packed with cotton and 12 ml of 99% ethyl alcohol measured into a medicine cup.

The alcohol was slowly added to the cotton with a disposable pipette until the cotton was thoroughly saturated. This would be allowed to evaporate overnight. The goal was to allow the alcohol to dissolve the residues and move them to the cotton as the alcohol evaporated. Since the stem was in deox overnight and the stinger was clean, I had only some Mark Twain reading to keep me occupied and sleep, of course.

The next day after lunch I returned to find the alcohol evaporated and the cotton stained.

The cotton was removed using forceps.

The cleaning of the shank proceeded again but much faster this time around.

I gave the leather a second coating of the Mink Oil and allowed it to absorb into the leather briefly before hand buffing with the athletic sock.

The stem was removed from deox and allowed to drip excess solution back into the jar.

A coarse shop rag was used to vigorously rub the stem to remove the loosened oxidized vulcanite and to absorb the solution. You can see from the stains on the rag how effective this was.

The stem was then scrubbed with Soft Scrub cleanser on make-up pads. One pad was used on each face of the stem.

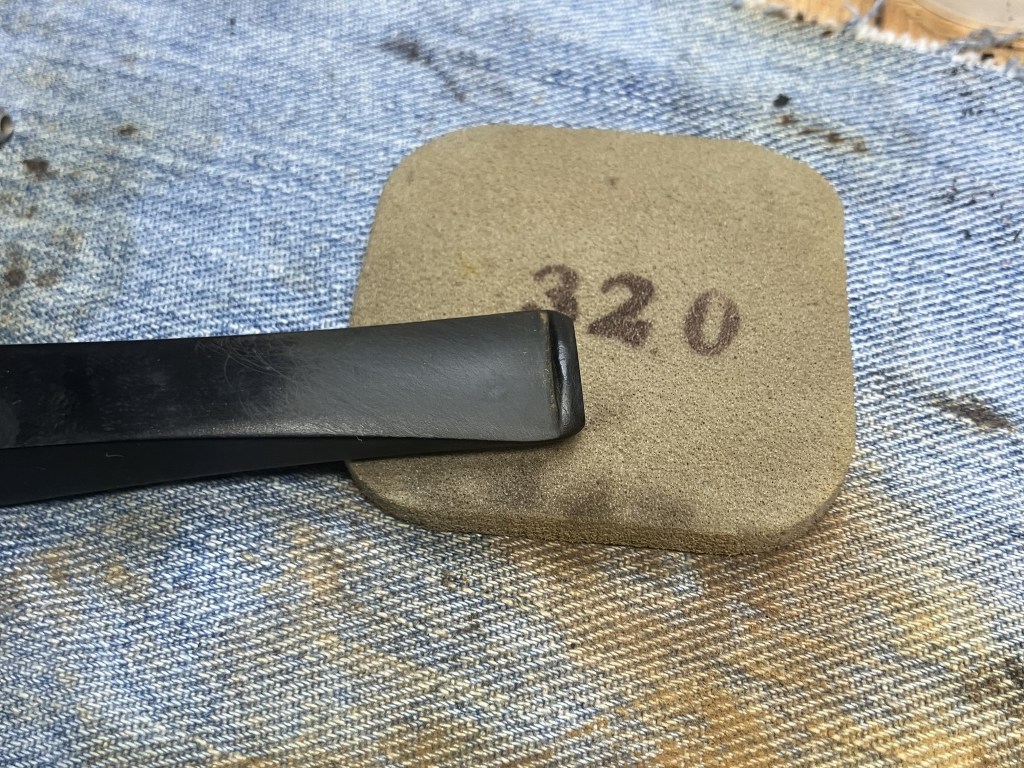

The bite zone, top and bottom, were sanded with a 320 sanding sponge.

I wanted to keep the squared shape as much as possible. To do this I used a piece of 400 grit sandpaper wrapped around a wooded block. This was in an attempt to keep the square shank preserved as much as possible.

Mineral oil was rubbed onto the stem and wiped from the stem with a paper towel.

The stem was then sanded with a series of sanding sponges from 600-3500 grits. Again, the stem was rubbed with mineral oil and wiped with paper towels between each sponge.

The stem was then worked with micro-mesh pads 4000-12000. In place of mineral oil, Obsidian Oil was used between micro-mesh pads.

The stem was then buffed with a blue buffing compound on a dedicated blue wheel on the buffer.

The stem was then given several coats of carnauba wax on the buffer.

The final step was to hand buff the pipe with a microfiber polish cloth.

I can’t say that I am a user of leather clad pipes, I actually don’t think I have ever tried one. I can appreciate their appearance and their feel in the hand. They do feel good with their softer texture and in this case the faux reptile skin texture. The stem of this pipe polished up very nicely; this is a credit to Jeantet’s use of quality vulcanite. The glossy black stem is a beautiful contrast to the rich brown leather and the briar rim looks very nice together. The stitching and seams of the leather are niche and tight and show little wear. The dimensions of the Jeantet Leather Clad Panelled Apple are:

Length: 5.88 in./ 149.35 mm.

Weight: 1.70 oz./ 43.18 g.

Bowl Height: 1.74 in./ 44.20 mm.

Chamber Depth: 1.42 in./ 36.07 mm.

Chamber Diameter: 0.73 in./ 18.54 mm.

Outside Diameter: 1.53 in./ 38.86 mm.

I do hope that you have found something here useful to your own pipe care, maintenance or restorations. If you like this sort of thing, please click the like and subscribe buttons. Thank you for reading the ramblings of an old pipe lover.

Below are some photos of the finished Jeantet Leather Clad Panelled Apple.