Photographed and written by

John M. Young

I just can’t stop myself from working on those darn 1940s pipes. This little gem is one of those World War II Mediterranean briar substitutes. Kind of like a substitute teacher, they try but just are not the same as the regular version. I’ll get to more detail on that in the Background section, below. I have restored a handful of Trapwell pipes over the years

and found them to be exceptional smokers. They all share the same system for cooling the smoke and condensing out steam. It is this system that makes them good smokers but also a bit troublesome to clean. The subject of this blog is a large apple that has seen some tough handling. The pipe was purchased through eBay and was not part of an estate lot, just a single pipe. After a journey from Union Dale, Pennsylvania to the wilds of southeast Nebraska the old girl arrived. Below are some photos of this Trapwell as she appeared prior to any work.

I am not all that familiar with pipe care practices in different parts of the country. Apparently in Pennsylvania, pipes are frequently placed into cages with hyperactive irate badgers. I could be wrong on this but it would explain the numerous gouges, scratches, dings, dents and other surface scars that the Trapwell had. There were also signs that the pipe was smoked in between badger treatments and perhaps tumble drying sessions with the previous owner’s rock collection. There was a definite lava accumulation on the rim and some caking within the tobacco chamber. The stem and band had marks along their length that indicated that the badgers of Pennsylvania have acquired the use of pliers. These tool marks indicated to me that the stem was probably quite stuck in the shank (It was). The stem also had a bit of tooth chatter which would have to be repaired. Overall, it looked like a fairly straight forward restoration (It wasn’t).

Background

To have an understanding of Trapwell, we have to look into their origin story. No, there are no radioactive spiders but it is still a good story. “Henry Leonard & Thomas, Inc. (HLT) was founded in Ozone Park, Queens, New York by Henry J. Lavietes and two partners on May 31, 1938. The company patented a stem design for pipes and cigarette holders designed by Henry on March 9, 1943. Henry was the son of David Lavietes, who moved to Sparta, North Carolina in the early 1940s to purchase laurel and rhododendron burl to ship back to his son and HLT. Lavietes decided to stay in Sparta and founded the D&P Pipe Works with his other son Paul, originally as a 15 person operation. David Lavietes was the inventor of the Ajustomatic feature incorporated into Dr. Grabow pipes even today.

In 1944, the trademark for the Royalton filter well was granted to HLT. Soon after, however, Henry Lavietes closed the New York operation with little warning and moved the entire production to Sparta, North Carolina. At this time in addition to the Royalton line, HLT was making many other lines of pipes.

In 1953, HLT acquired all assets and equipment of the Dr. Grabow company of Chicago, Illinois, and began production of Grabow and Hollycourt pipes. At the same time, they acquired the Continental Briar Company, owner of the Royal Duke, Duke of Dundee, and Honeydew pipe brands still evident in the common use of the word “Duke” to name Grabow pipes.

On October 21, 1969, United States Tobacco company, owners of the Mastercraft brand, announced that it had acquired HLT. It still ran as a separate company until 1985, however, when Sparta Pipes, Mastercraft and HLT were merged into Sparta Industries, Inc.

While, even after this time, the HLT brand was sold to Lane, and later, in 2006 to International Pipes & Assessories, the current owners, IPAL continues to make and sell the Royalton pipe with the original HLT logo as part of the Grabow line.” (Henry Leonard & Thomas Inc. – Pipedia) (Italics are mine)

So we have David Levietas and son, Paul, setting up a North American briar harvesting venture in North Carolina. All of this due to the Nazis waging war on Europe and shutting down exportation of the pipemans’ favorite wood – briar. That dynamic duo was D&P Pipeworks.

“Trapwell pipes marked with “World’s best briar” are made of Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) a species from the Ericaceae family.

The brand was made by D & P Pipe Works, owned by D. P. Levitas and located in Sparta, Alleghany County, North Carolina close to the population of Mountain Laurel in the area. Later, this company changed its name to Sparta Pipe Works and still later to Sparta Industries.

There were at least three pipe brands made from the Mountain Laurel: Trapwell, Breezewood and Custombilt.” (Trapwell – Pipedia)

David Levietas, as previously mentioned was the inventor of the “Ajustomatic”. He also was the inventor of the Trapwell system. The below diagram from the original US patent 2,262,159 was screenshot from the PDF. This PDF can be found here: US2262159A – Smoker’s pipe – Google Patents for those interested in the original.

The text of the patent was also saved as images and is included below. Again the original PDF can be seen here: US2262159A – Smoker’s pipe – Google Patents.

It is this feature that makes the Trapwell pipe what it is – a fine smoking tool.

The Restoration

This restoration began with me attempting to unscrew the stem from the shank of the pipe. This unscrewing actually removed the aluminum mortise from the shank. This was not an intended part of David Levietas’ design. From the photos above you can see the following images:

The photo on the right is what is supposed to happen when unscrewing the stem. Using a pliers with the jaws wrapped in painters tape, as to not mar the stem nor aluminum, I was able to unscrew the two aluminum threaded parts. I would have to reinsert and glue the mortise section back into the shank. This comes later in the restoration.

I set out cleaning the threads of the tenon by soaking the threads in 95% ethyl alcohol. The threads were then scrubbed with a brass brush dipped in the alcohol. This cleaned any residual tars and removed most of the oxidized aluminum.

The shank piece of aluminum was larger and required a larger medicine cup for soaking. It also required more alcohol. I opted to use 91% isopropyl alcohol for this larger amount. Yeah, I’m cheap. Isopropyl is far less expensive than ethyl. That extra carbon and two hydrogens of the isopropyl must reduce both the effectiveness of it as a solvent and the cost. It still worked to clean the aluminum along with cotton swabs and bristle pipe cleaners.

The stem was cleaned out with 95% ethyl alcohol and bristle pipe cleaners.

With the insides clean it was time to address the exterior. I lightly sanded the stem with a 320 and 400 sanding sponge. I then painted the tooth chatter with a lighter in hopes of raising the dents.

The sanding and flame painting helped with the tooth chatter but were unable to do much to the pliers scars. These would require filling with black cyanoacrylate (CA, super glue).

I switched tasks to the stummel. Yeah, ADHD isn’t just for kids. I gathered the reaming tools and started working on the tobacco chamber. This was a relatively narrow chamber and would not fit my PipNet Reaming tool since I had broken the smallest size blades for it. The Scotte Stainless Steel reamer would suffice.

Looking down into the chamber I couldn’t see any damage from heat. It still needed additional scraping and sanding but still the Mountain Laurel appeared to be heat resistant. Not the badger claw marks through the lava.

Next the stummel was taken to the sink. Here it was scrubbed with undiluted Murphy Oil Soap and a medium toothbrush. The soap was rinsed with warm water and then the stummel was dried with a cotton hand towel.

Back at the workbench you can see the grain of the Mountain Laurel. It is different from briar and lacks the bird’s eyes. I can’t say that it is unattractive, just different.

I wiped the surface with a make-up pad dipped in 95% ethyl alcohol to remove any wax and or finish from the stummel. I got some color on the pad. It looked more like a stain than a finish.

The stummel was then sanded with a 320 and a 400 grit sanding sponge.

The rim needed topping to address the dents and dings on the surface. This was done with a piece of 320 sandpaper laid flat on a countertop. I used a circular pattern with rotations of the stummel in my hand every 3-4 circles. This process was repeated with 400 grit sandpaper.

In preparation of a contrast dye, I taped the stamps to keep them from being as heavily dyed as the stummel. The tape was cut in irregular patterns to avoid the blocky appearance when finished.

I planned to use a mixture of ⅓ black to ⅔ dark brown Fiebing’s Leather Dye.

The dye was measured out with a disposable pipette and mixed in a medicine cup. It was then applied to the stummel using a bent pipe cleaner as an applicator. The wet dye was flamed with a lighter to burn off the alcohol solvent of the dye.

The stummel was then rinsed with 91% isopropyl alcohol over the sink.

Excess dye was wiped from the stummel with a paper towel. The protective tape also came off during the wiping but it had done its job.

Back at the workbench the stummel was wiped with a couple of make-up pads dipped in 95% ethyl alcohol. I was not sure how the Mountain Laurel would take the dye as I had never dyed Mountain Laurel before. The softer portions of the wood absorbed the dye very well while the harder grain seemed to repel the dye to some extent. This looked to give the wood a very interesting pattern.

I then tried to sand off the outermost black dyed layer of wood. It was here that I realized how woefully inadequate my previous sanding had been. The badger claw marks were everywhere. Stupid badger.

After thinking about how to deal with the scratches and dents for what seemed like hours, I thought, “try steaming them out”. I plugged in the iron, set it to high, wetted a washcloth and donned a left glove. I wrapped the washcloth around the stummel and proceeded to roll it over the hot iron. I would have taken pictures of this process had I more than the two hands.

The results of the steaming were better but still required far more sanding. And yes, it’s a kevlar glove, I clean fish down at this sink on occasion.

Okay, back to sanding. Lots of sanding. And then some more sanding.

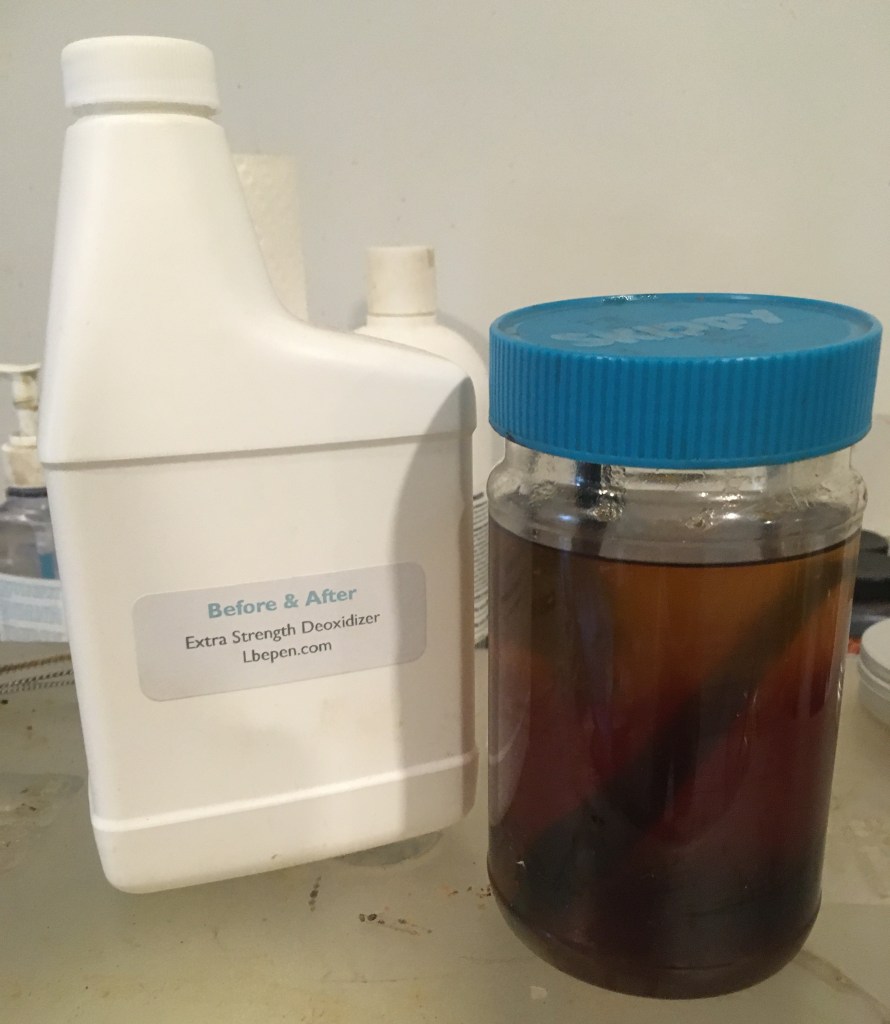

Finally I was wondering if I had done so much sanding that the contrast dye had been completely removed. Out of curiosity I grabbed the Before and After Restoration Balm and gave the stummel a coating. I waited 15 minutes for the balm to do what it does – magic. Many of the dents and scratches seemed to have disappeared.

There were a couple of dents that were too much for even the wonders of Restoration Balm. These would have to be filled with brown CA and briar dust. Now that I write that I realize I should have used Mountain Laurel dust. I certainly had enough.

The new fills were filed with a flat needle file then smoothed with 400 sandpaper.

I must have left stummel mode and entered CA fill mode. I started filling the tooling and tooth dents on the stem. Here I used black CA and spritzed it with a CA drying accelerator.

These areas were again filed flat with a flat needle file then smoothed using a 400 grit sanding sponge.

For a final finish I applied a light top coat of thin clear CA. This CA flows more easily and filled any small depressions that remained. Once cured the areas were filed and sanded as above.

The wood of the shank was taped with painters tape and the stem was sanded using a series of sanding sponges from 400-1500. Between each sponge I dabbed mineral oil onto the stem, rubbed it in with my fingertip and wiped the stem with a paper towel.

The above was repeated with the 2000-3500 sanding sponges.

The stummel got new tape over the stamps. Then was sanded sith the sanding sponges 1000-3500. Between sponges I wiped the wood with a make-up pad moistened with alcohol.

The tape was removed and the adhesive wiped off with alcohol. The pipe was then polished with the micro-mesh pads 4000-12000. The stummel was wiped with alcohol on a make-up pad between pads. The stem received a drop of Obsidian Oil, rubbed onto the vulcanite and a wipe with a dry paper towel.

Once finished with the micro-meshing I pulled the aluminum shank insert out. Cleaned the hole and the aluminum with a cotton swab dipped in alcohol then applied a light coat of white all purpose glue to the toothed end of the aluminum and reinserted it into the shank. I adjusted the bit while the glue was wet. The joint where the two pieces meet was wiped with a paper towel and a bit of alcohol. The pipe was then taken to the buffer for several coats of carnauba wax.

This Trapwell Apple turned out far better than I thought it would. During the restoration I still had my doubts as to how it would look finished. It is truly a stunning pipe. Some of the scratches are still evident but the Mountain Laurel nearly has a glow to it. In sunlight it is remarkable. The contrast dye did far better than I hoped it would, even after all my post-dye sanding. The stem polished up nicely as well. There remain some deep scratches in the aluminum but removing them would probably alter the straight smooth shank to stem junction. Overall I am very pleased at how this pipe turned out. The dimensions of this beauty are:

Length: 6.11 in./ 155.19 mm.

Weight: 1.34 oz./ 38.00g.

Bowl Height: 1.47 in./ 37.34 mm.

Chamber Depth: 1.26 in./ 32.00 mm.

Chamber Diameter: 0.68 in./ 17.27 mm.

Outside Diameter: 1.56 in./ 39.62 mm.

I do hope that you have found something here useful to your own pipe care, maintenance or restorations. If you like this sort of thing, please click the like and subscribe buttons. Thank you for reading the ramblings of an old pipe lover.

Below are some photos of the finished Trapwell Large Apple.