Photographed and Written by

John M. Young

I was recently approached by a fellow member of the Facebook (FB) group The Real American Pipe Smokers (RAPS) to repair a chipped button on a Stanwell bulldog. The pipe’s owner, named Cash, had shown the chipped stem to other restorers or repairmen and they recommended stem replacement. Very understandably, Cash did not want to lose the brass inlaid Stanwell stem. I said that I thought that I could repair the chipped button making it usable again without a stem replacement. I do love a challenge. Cash and I never discussed the cost of this project.

Shipping was arranged and Cash sent the pipe off from Alabama to the wilds of southeast Nebraska. When the box arrived I was surprised by the size of the box. When I lifted it I was even more surprised by the weight. I wondered if a new packing material had been developed in Alabama which would replace the air filled bubbles with tungsten. Upon opening the box I was astounded by the number of pipe tobacco tins that had been included for me to sample. I immediately replied to Cash saying, “Good Lord, man. You sent me enough tobacco for a couple of full restores. Thank you so much. I have always wanted to try a couple of those. I am plotting a couple of “best ways” to fix the Stanwell as I type.” Cash’s reply spoke to his generosity, “Sharing is part of the fun and enjoyment of it haha. Glad you like it, can’t wait to see what you come up with for the pipe.”

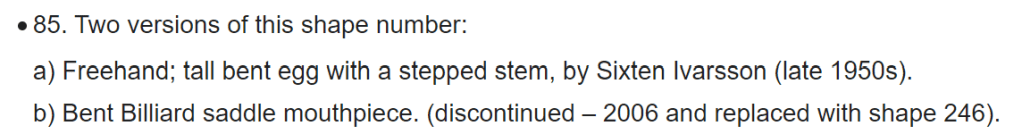

The Stanwell was a delightful 02 shape. The shank had a double brass band separated by a zebra-wood band (I think it is zebra-wood). The stem was a polished acrylic with an inlaid S topped with the Stanwell crown. It was a stunning pipe. A stunning pipe that had a chipped button problem. There was also tooth chatter on both the top and bottom of the bite zone. This was a well loved stunning pipe. Below are some photos of the pipe prior to any work done.

The only significant issue was the chipped button. Other than that the pipe was in very good and very clean condition. Sure there was some tooth chatter on the stem which I would remove and a general cleaning followed by some polish and waxing. The stem repair was the reason for the commission.

Background

I will not bother you with a history of Stanwell pipes. If you are interested in this truly illustrious brand, I will include a link here: Stanwell – Pipedia.

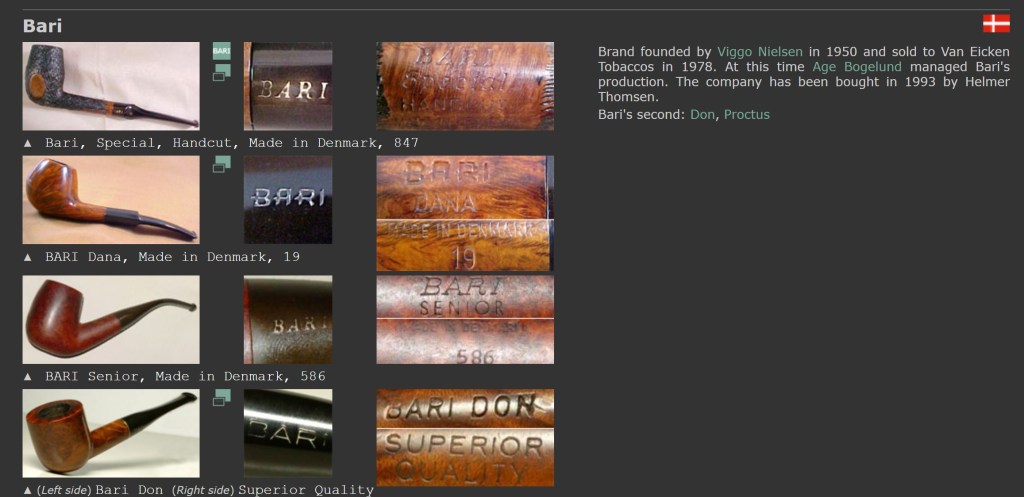

This pipe is one of the oldest shapes in the Stanwell line-up. According to pipedia.org’s Stanwell Shape and Designer page,

“32. Two versions of this shape number:

a) Straight bulldog with a saddle stem; Stanwell’s first pipe shape (originally designed in 1942).

b) Bent Dublin-strawberry hybrid with a rounded rim and saddle stem, by Sixten Ivarsson. Redesigned by Tom Eltang in the early 1990s.” (Stanwell Shape Numbers and Designers – Pipedia).

This pipe is most certainly a member of the “a” club.

The Repair

The chip, which is the focus of this repair, spanned the lower button. With a normal repair I would have thought about bridging the span with a 2 mm brass rod set into the button then overlaid the brass with layers of black cyanoacrylate or black epoxy to conceal the brass. Finally reshaping the button back to its original shape. The Stanwell button, with a smaller, more delicate button had less material in which to conceal a 2 mm brass reinforcing rod. Now the pressure was really on me. I remember lying in bed thinking about potential repairs:

- The standard black cyanoacrylate material build-up and reshaping.

- An epoxy material build-up and reshaping.

- Using a brass pin to reinforce the button underneath the new material.

- A new idea formed in my sleepy brain, this stem is acrylic. What is the melting point of acrylic? What if a sample of black acrylic were to be melted and that was the source of the new material/replacement material build-up? Hmm, something to think about while more awake. Molten black acrylic material build-up and reshaping.

The next morning I researched the melting point of acrylic or Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) specifically. (Acrylic Melting Point | A Comprehensive Guide) According to this site the melting point was dependent on additives, which would alter the physical properties of the plastic by changing the flexibility, glossiness, hardness, etc… In general the melting point was about 320 degrees Fahrenheit. That was a relatively easy temperature to work with. I immediately started thinking about ways to achieve and maintain that temperature. I did not relish the thought of running my oven in the heat of August but this was for science!

Option 4, was seeming like more and more of an interesting potential solution. I would definitely want to test the technique on a guinea pig stem before trying on Cash’s Stanwell. I may have been born at night but not last night. I knew that this was all just an idea between my ears. One of the benefits of having no formal training in pipe restoration is that I have no set or “right” way of doing a repair. I reached out to Steve Laug and asked him if he had ever heard of using molten acrylic to rebuild a stem.

Sidenote:

Now, you are probably wondering if this is going to be a blog about repairing an acrylic stem using molten acrylic. Well, at this point, I had no idea. I was just waiting to hear back from Steve.

A return to critical thinking and scientification, Steve got back to me and said, “Yes. But have never tried it” (Laug, Steve. Personal communication). Hmm, Steve had heard of this idea. Good thing I didn’t say, “A return to original thinking and scientification.” He did make a good point though, I wondered “how will the molten plastic affect the hard cool acrylic I put it on.” That made me think that heating the receiving stem to around 280F would be a good idea. Why 280F? I don’t know, but it sounds good. Okay, enough thinking, time for some doing.

As if by coincidence and not by some algorithm the following link came up on my computer later that same day:

Beginners’ Guide to Melting HDPE – How to Make a Recycled Plastic Pen

Not being one to give credit to conspiracy theories, I thought why couldn’t Al Gore write a better computer program and hook me up with a more appropriate “Repairing a Chipped Acrylic Pipe Stem Using Molten Acrylic” article. Maybe he is too busy saving the world from global warming or shopping for additional sea side properties and just had some lackey intern write it for him.

Another sidenote: In the previous blog: A Royal Danish 913 Pear Restoration – NebraskaPeteGeek I discussed and photographed the process of collecting acrylic material from fitting a new acrylic stem to replace a damaged vulcanite stem. This was the source of acrylic for the next portion of my experimentation.

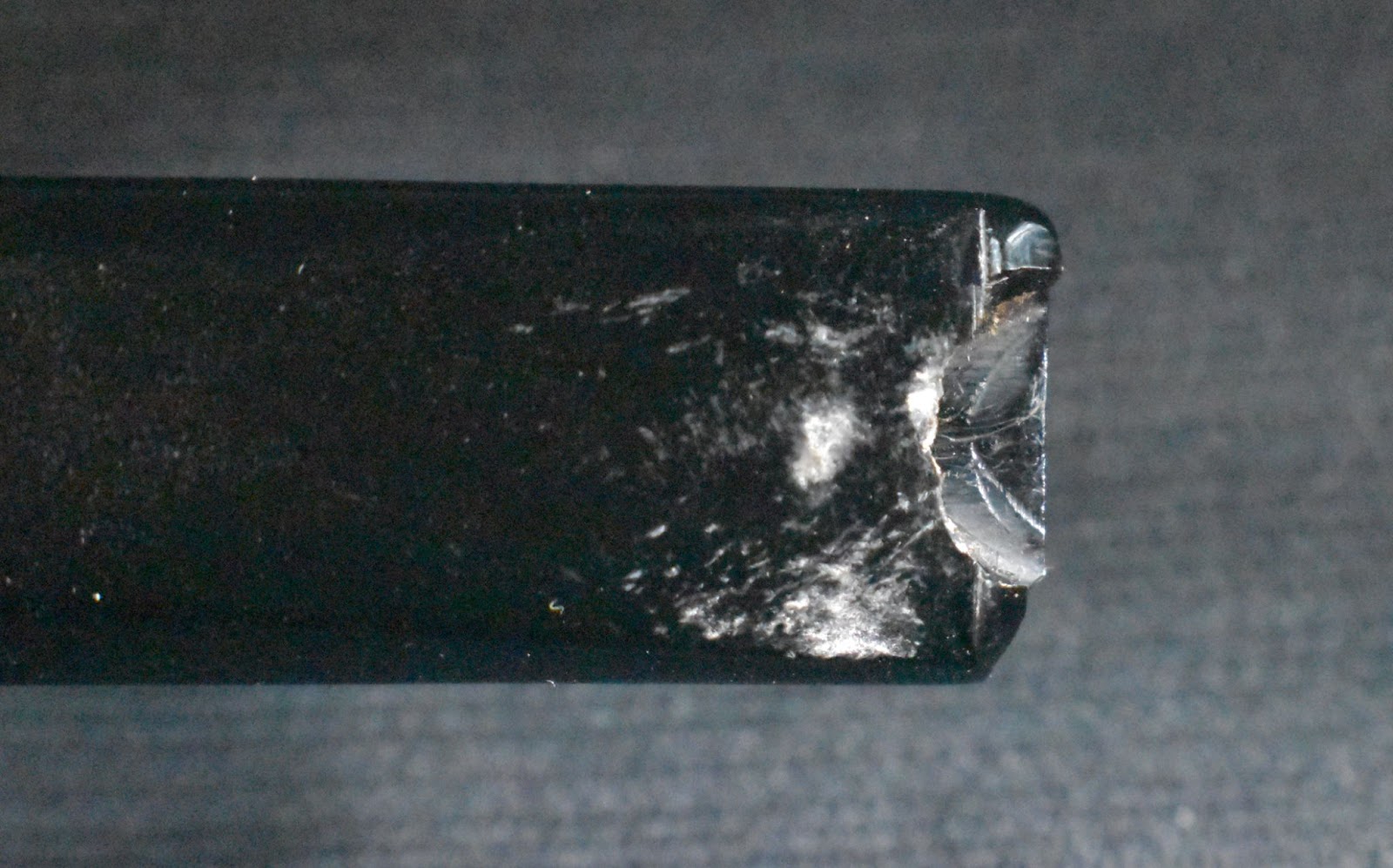

I turned my scientificating brain toward the melting of the acrylic turnings I had generated. One article said that acrylic melted at 320℉. I set the oven to 320℉ and placed the snuff tin with acrylic shavings on a parchment covered pizza pan into the oven. I expected the acrylic to melt like a thick liquid like hot tar.

It didn’t. Hmm.

I raised the temperature10℉. And continued my expectation. Expectation dashed.

I raised the temperature to 340℉. At this point expectations were still alive though some life support may have been required. Another 10 minutes and another dashed expectation. Hmm.

I tried raising the oven temperature to 360℉. Still nothing, though the acrylic shavings were far more pliable (when poked with a knife) and seemed to be kind of flattening on the snuff tin. Hmm.

380℉ Seemed like the next logical step. Would you like to guess what happened? If you guessed nothing you would be quite correct. Running the oven for over an hour in August was proving to be another in a long list of poor choices that I had made. I called it quits, turned off the oven and left the acrylic in there until morning.

The next day I thought that maybe a small soldering iron would be a better tool for melting acrylic. My imagination ran through various unfounded thoughts. I decided that the imagination needed to take a back seat to good old scientification trial and error with an emphasis on error. Not wanting to try anything new and untested with a client’s pipe, I set out to practice on a sacrificial pipe stem. An acrylic test victim was selected from some pipe stems I had. Using a screwdriver, I broke out a portion of the practice stem. I then used a Dremel rotary tool and cut a gash into the button as well. This gave me two areas to attempt repairing with molten black acrylic and a soldering iron.

Using a pencil electric soldering iron, I applied the heated tip to the acrylic turning. They melted and stuck to the tip. I thought, “Success”. Now to transfer this material to the area on the practice stem. It transferred pretty easily. Two problems quickly became evident though:

- The turnings were full of air pockets as they were like ribbons or shavings.

- I wanted to make sure and melt the original stem acrylic also to bond the new and old together.

Solutions:

- I found that by pressing the soldering iron down and rolling the tip, I could force the turnings into place and press out possible air trapped in the acrylic. There could still be unseen bubbles that would only be discovered when pressure was applied to the stem from biting down on the button and cracking through the thin unseen bubble.

- I tried heating the original stem, melting the new and old acrylic together. That worked

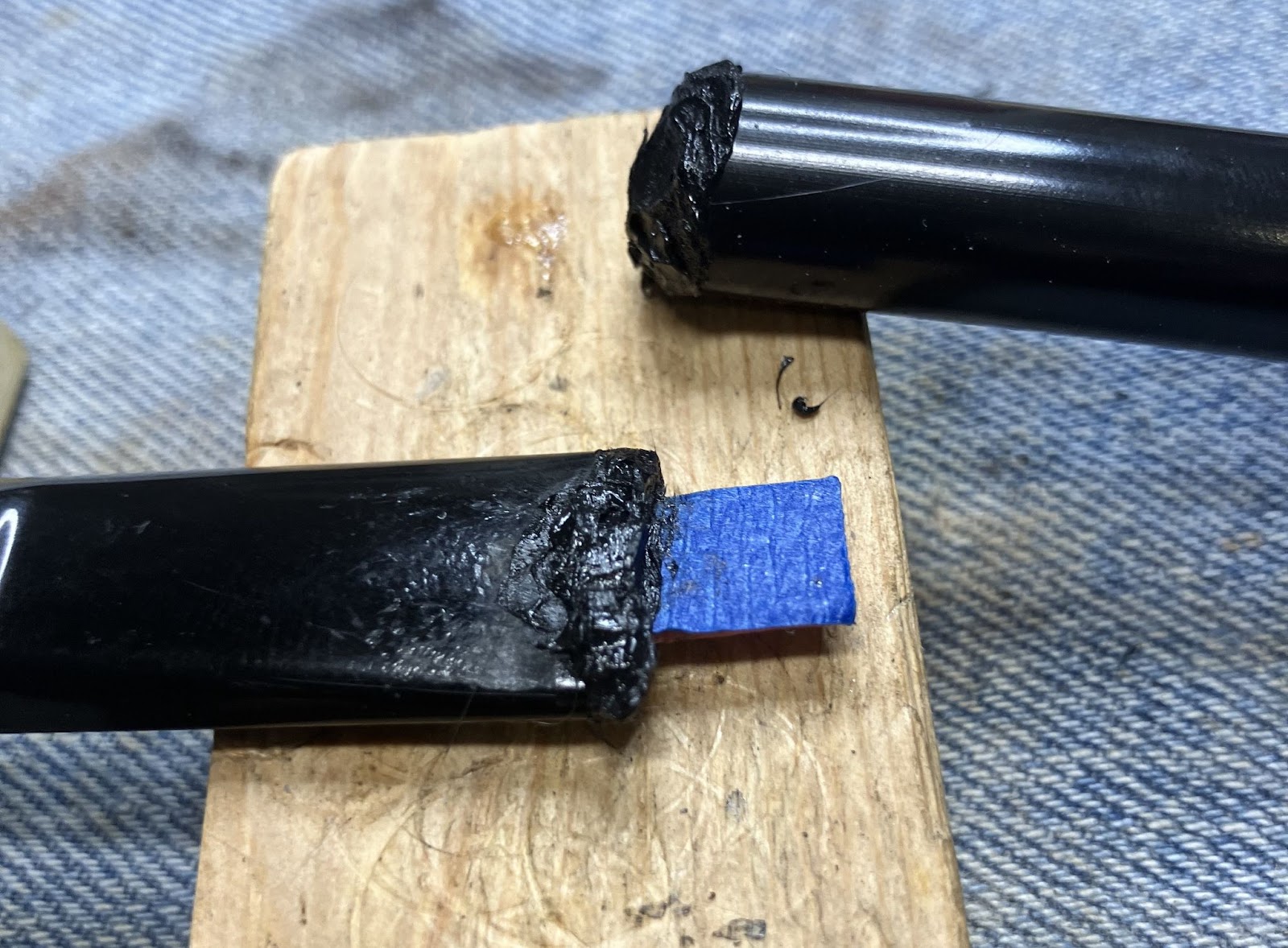

I failed to photograph the developing soldering iron techniques but did take a few photos of the “welded” practice stem. The first two photos below show my attempts to fill the voids and file the added acrylic with a small flat file, reshaping the button.

The third photo shows the same fill but here I had gone over the previous fill and remelted the filled area and added additional weld acrylic. I tried to press the new material into the existing material with more force, hopefully pressing out any air pockets and smoothing the weld more than the previous attempt. The button was reshaped using the same file.

The rebuilt patch was finished with an application of black cyanoacrylate (CA, super glue).

The CA was spritzed with a cyanoacrylate drying accelerator. This made the CA harden almost immediately. The hardened CA was then shaped with a small flat file and sanded.

The airway was rough. Unseen air bubbles within the weld were probably responsible.

I used a Dremel rotary tool and a small cutoff bit to reshape the end of the button.

Below is the reshaped button.

After further sanding and polishing, the stem repair looked pretty good.

A scar of the repair was visible, but only upon close inspection.

Below are two photos of the polished button.

I tested the fill by biting done on it simulating normal force applied during clenching. The fill seemed solid. I was and still am unsure how the weld will hold up over time and extended clenching.

Yet another sidenote: I am sure that you are wondering, “Good lord, man. 41 pages in and you still haven’t started the repair on this poor guy’s pipe!” Hmm, I wonder if I was a bit frightful of doing irreparable harm to the Stanwell?

I sent my preliminary findings and photos to the client, Cash. I wanted his opinion regarding this as a possible repair solution. He consented to the application of melted acrylic. More pressure but at the same time I thought I was onto a very workable solution to the problem at hand. One thing I had ordered since I started this project was a couple of ½ inch rods of black acrylic. I thought that the rods might be useful as a source of acrylic welding material where I did not have to deal with the problems with the turnings, aka, air bubbles within the weld.

The moment of truth had arrived. I was going to use the new black acrylic rods as a source for acrylic to fill the void in the Stanwell. I plugged in the soldering iron and patiently waited for it to heat. Testing the soldering iron on the acrylic rod allowed me to gain a feel for how the acrylic melted and the pressure I needed to shape it.

I had previously cut a plastic lid and applied layers of painters tape to thicken it until I had the thickness I wanted. This would act as a dam and provide a surface on which I could weld to while filling the void left by the chip.

I cleaned the shipped stem with bristle pipe cleaners dipped in 99% ethyl alcohol making sure to carefully clean the broken surfaces. I also examined the area to make sure no pipe cleaner fibers were present.

With the dam in place and a feel for the melting of the acrylic rod, I was as ready as I could get to try welding with someone else’s pipe. I started melting material from the acrylic rod and moving it to the stem. Once there, I worked the material with the tip of the soldering iron into the existing stem acrylic by heating both and melting them together. Additional acrylic was added to fill the void again, remelting applied material and adding new. Yeah, at this stage it was quite ugly.

Slowly this process built up acrylic into the void.

The dam was removed to check its performance. Below you can see through the airway.

Once sufficient acrylic was added, it was time for some button reshaping. I used a small flat file, emery board and a 320 grit sanding sponge for the reshaping. Below is the stem top view.

And here is the stem bottom where the majority of material had been added. There were a couple of spots where additional acrylic was needed.

While doing the reshaping of the button a chip of new acrylic broke off from the button on the left side of the below. This re-emphasized that I needed to re-melt the existing material when applying additional acrylic to get the two layers to bond.

I used the soldering iron to create a narrow point of melted acrylic on the acrylic rod’s end to aid in the application of additional material to the stem. I wondered if an ⅛ inch diameter acrylic rod was available. This would be much more useful in future projects..

Below is the button after the second application of more acrylic.

Below is a photo of the end of the button after the second application.

And the bottom of the button after the reshaping of the second application.

Below is a stem top view of the reshaping after the second application.

The shape was getting there. In the below photo you can see seems where air bubbles were present. The end would need further sanding and a bit more shaping.

Eventually I had to call it quits on the shaping. There remained some small flaws in the new acrylic. To fill these, I chose to apply a thin coating of black CA. I hoped this would flow into any small seams and bubble voids. The CA was allowed to cure on its own for an hour.

Once fully cured the CA on the top and bottom was filed smooth with a small flat file.

The filed CA looked good and was only noticeable with close examination.

I wanted to clean up the slot at the end of the button. I did this, as with the practice stem, using a Dremel rotary tool and a small round cut-off bit.

The stem was then sanded with a series of sanding sponges in grits of 320-3500. I saw no reason to sand the stem above the saddle so it was not sanded. Between each sponge I wiped any sanding debris from the stem with an alcohol wetted cotton ball.

I proceeded to work the stem with 4000-12000 micro-mesh pads. Here I worked the stem along the full length. I applied masking tape to the shank to avoid any damage to the stamped areas. Again, between each pad I wiped the stem of any debris between pads.

The masking tape was removed and the pipe taken to the buffer where I buffed the bands and stem with white buffing compound. The next two photos show the stem, top and bottom, after buffing.

And the button after buffing.

I cleaned the airway of the shank with a nylon shank brush, bristle pipe cleaners and cotton swabs all dipped in 99% ethyl alcohol.

The tobacco chamber was reamed with the standard ream team.

The narrow chamber of the Stanwell only allowed the #1 blade of the PipNet with the remaining work done by the Smokingpipes Low Country reamer. I did not take the tobacco chamber back to bare briar and left a thin layer of cake.

The rim had a light layer of lava.

I moistened this with saliva and carefully scraped it with a sharp pocket knife blade.

The stummel was then wiped with an alcohol wetted cotton ball to remove surface dirt and grime. Most of this was probably deposited by me.

The stummel then received a coating of Before and After Restoration Balm which was allowed to do the magic that it does for 15 minutes.

The balm was removed by a hand buffing with an inside out athletic sock.

The pipe was then taken to the buffer for several coats of carnauba wax. The final step was a hand buffing with a microfiber polishing cloth to further raise the shine.

Well, there it is. The repair of a pipe stem by welding black acrylic onto a chipped stem. The page counter says 92 pages. If you stuck through the whole thing, thank you. I had my doubts that it would work. In the end, I think it worked quite well. I am glad to know that I now have another tool in my toolbox for repairing pipes. I am imagining using this technique of vulcanite, as I type this. I’m also glad to know that Cash was very pleased with the photos I sent him of the finished pipe. I have no idea how many hours were spent on this project. Given, a good deal of it was practicing on a sacrificial stem and not actually working on the Stanwell. I consider Cash’s account paid in full, with all of the wonderful tobacco he sent me. Besides, how else was I going to learn a new trick? Now don’t get crazy and say, “You should be paying him for this opportunity.” Don’t make me stop this blog and spank you. (That’s what my dad always used to say to me when I was brothering/bothering my little sister, in the car. Except, not the “blog” part) The dimensions of this Stanwell 32 are:

Length: 5.00 in./ 127.00 mm.

Weight: 1.32 oz./ 37.42 g.

Bowl Height: 1.80 in./ 45.72 mm.

Chamber Depth: 1.48 in./ 37.59 mm.

Chamber Diameter: 0.69 in./ 17.53 mm.

Outside Diameter: 1.53 in./ 38.86 mm.

I do hope that you have found something here useful to your own pipe care, maintenance or restorations. If you like this sort of thing, please click the like and subscribe buttons. Thank you for reading the ramblings of an old pipe lover.

Below are some photos of the finished commissioned Stanwell 32.